“I will always be an Indian.”

“My mom was an Indian, my sister was an Indian and I want to be an Indian too.”

To the white students in northern Wisconsin contesting the removal of their Indian mascots the claim of Indian identity is sincere. And this sincere attachment to an invented image of “Indian” provides a key to unpacking how whiteness is performed and maintained.

In his book Contesting Constructed Indian-ness, Michael Taylor explains how these constructions revel more about the creator than the people supposedly represented.

“In constructing a critique of Native American-based mascots and their uses by mainstream popular culture, the theoretical frames of whiteness, masculinity and place locate the research’s data which seeks to tell of how the meanings embedded in mascots are predominantly white society’s creations which reflect the ideas such as conquest, colonialism, dislocation, dispossession, identity, tradition, nationalism, and rhetoric back to its creator’s eyes”.

To further understand this particular construction of whiteness, and what it can teach us, I mapped a journey through northern Wisconsin that traversed a path between small towns with Indian mascots and Native American reservations.

Specifically, I wanted to think through how (if at all) the tensions and anxieties bound up in mascots are reveled in the physical landscape. How does the emotional distance between self and other manifest? And what does the shared space between imagined and embodied realities look like?

These questions of landscape and shared physical space are important because a crucial aspect of whiteness is identification with access to power rather than location. Whiteness does not refer to a geographically specific region but rather a system of domination and control. The location of Whiteness is in the imagination not in a particular homeland.

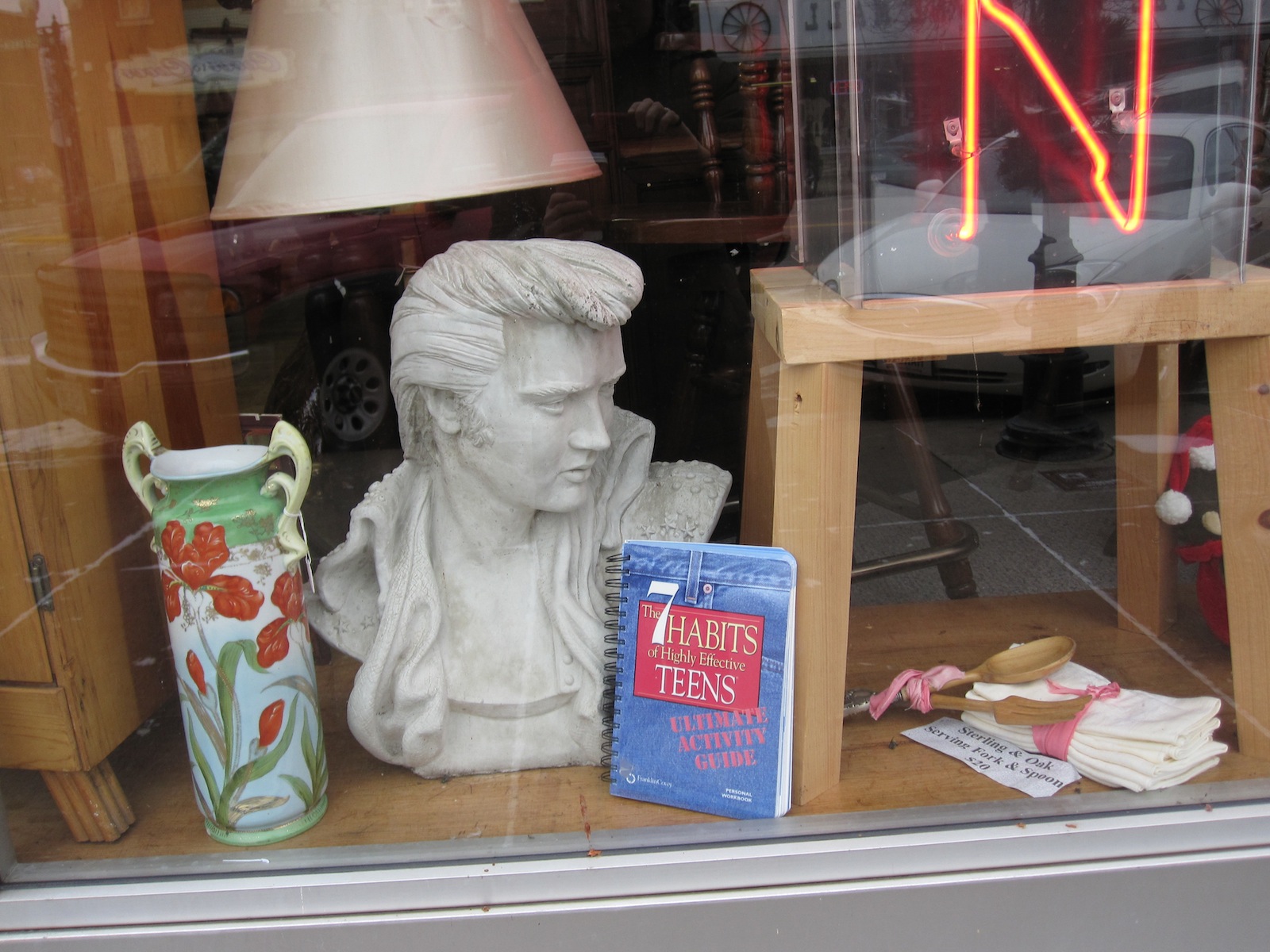

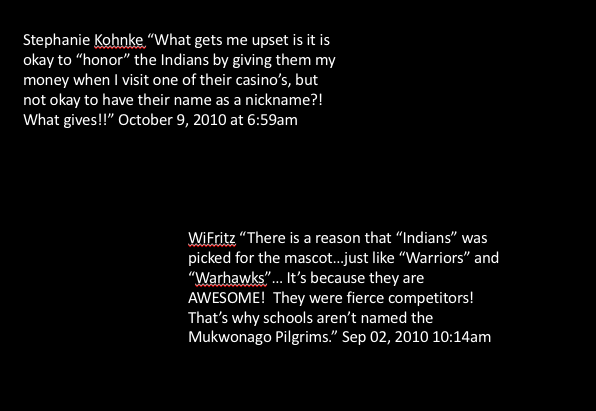

Importantly, the landscape of northern Wisconsin is where I grew up. It is, I would say, my homeland, and evidence of the white imagination is everywhere. While attempting to unpack the complicated relationships between self and other my particular intimacy with this place is significant. The images that best articulate my journey make visible what we are taught not to see; a crew of white fairies hanging next to an Indian rattle at the drug store, white characters used in storefront window displays as neutral avatars, all surrounded by the beautiful rural landscape that no doubt enchanted all previous generations.

The photographs are the background for an installation and performance in which a character named Whitey, who represents the existence of our colonial past, moves through the space, tracing outlines of Indian mascots and re-writing words pulled from Facebook groups on, over, and in between the images. All the while an enthusiastic crowd cheers her on.