Being haunted draws us affectively, sometimes against our will and always a bit magically into the structure or feeling of a reality we come to experience, not as cold knowledge, but as a transformative recognition.( Gordon, Avery. Ghostly matters: Haunting and the sociological imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.)

The photographs, paintings, and collages in What Light Knows are the result of a three year collaboration with nine ghosts; nine women who died in the Highland Hospital fire in 1948. Each of them were sedated and locked in their rooms at the time of the fire, deemed “unfit or wonderers”. Highland Hospital specialized in treating people who had been diagnosed with hysteria or what was then called nervous disorders. These diagnoses were frequently assigned to outspoken women with inconvenient opinions or passionate emotions.

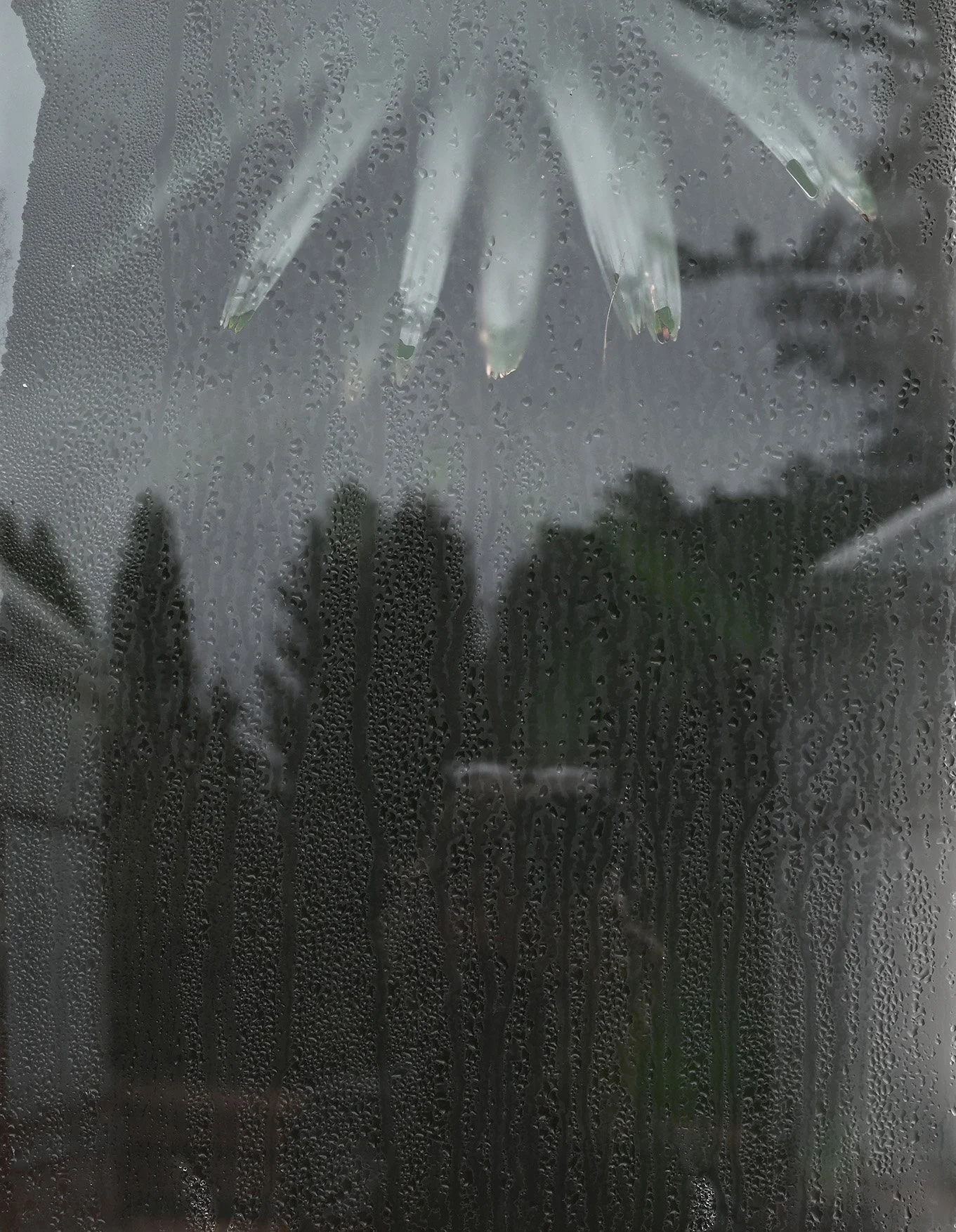

The collaborations began with long exposure photographs shot at the former sight of Highland Hospital, located less than a mile from my home in Asheville, North Carolina.

I would shoot the images intuitively, often not viewing what had been captured until returning to my studio. The images were not always beautiful but they did always surprised me.

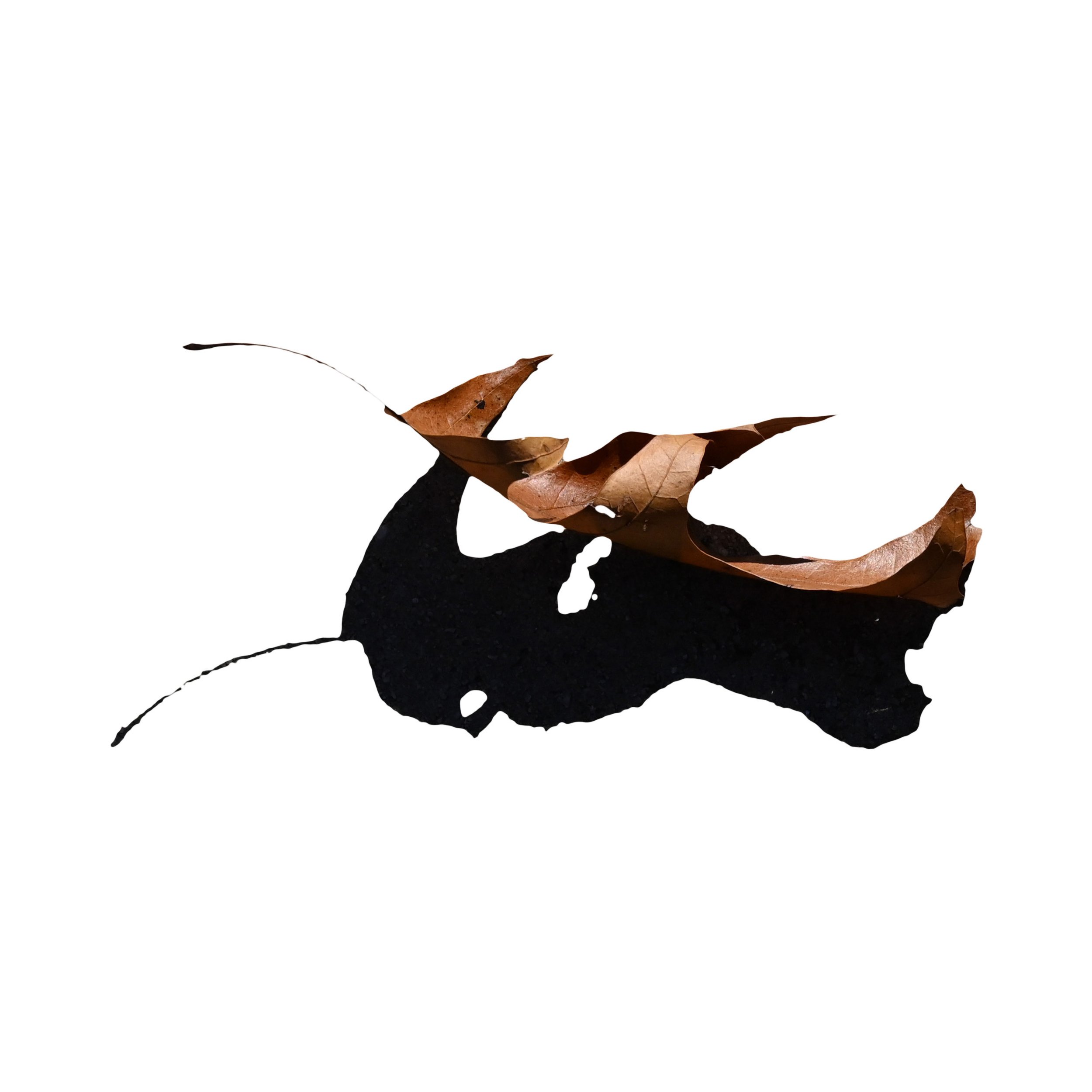

The strange animated light forms in the photographs compelled me to start creating collages and painting – a practice I have not engaged with for over 10 years. The expressive wildness in the photographs encouraged a wildness in my mark making and pallet choices.

This body of work is an invitation to ask stranger questions, observe what may seem to be invisible, and acknowledge the many ways we are haunted.

I am grateful to my collaborators: Miss Janice R. Borochoff, Miss Marthina DeFriece

Mrs. Jules Doering (nee Mildred Belton), Mrs.Ida Engel (nee Ida Levi), Mrs. F. Scott Fitzgerald (nee Zelda Sayre), Mrs. Allen T. Hipps (nee Sarah Neely), Mrs. Virgina W. James ( nee Virginia Ward), Mrs. W. Bruce Kennedy (nee Ethlyn Avirette), Mrs. Gus C. Womack (nee Martha Oma Thompson).